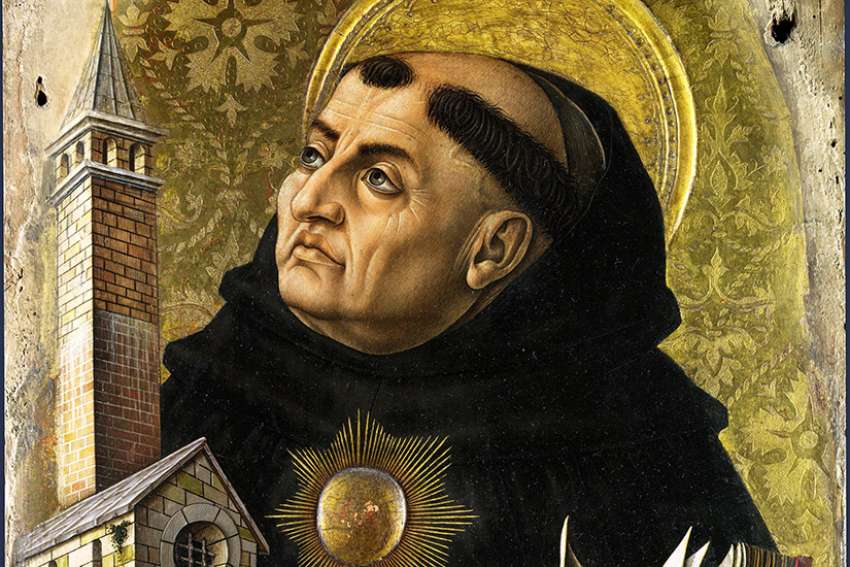

| Nothing could be more explicit: “Go to Thomas!” This warm invitation was issued by Pope Francis to participants of the International Thomistic Congress (Sept. 21-24) during an audience at the Vatican. In his address, the pope extolled the thought of Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) as a sure guide for Roman Catholic faith and a fruitful relationship with culture. Citing Paul VI (Lumen ecclesiae, 1974) John Paul II (Fides et ratio, 1998), who had magnified the importance of Thomas’ thought for the contemporary Roman church, Francis stood in the wake of recent popes in emphasizing superlative appreciation for the figure of Thomas while adding his own. |

This is nothing new. For centuries, Roman Catholicism has regarded Thomas Aquinas as its champion. His voice is often considered the highest, deepest, and most complete of Roman Catholic thought and belief. Canonized by John XXII as early as 1323, he was proclaimed a doctor of the church by Pius V in 1567 to be the premier Roman Catholic theologian whose thinking would defeat the Protestant Reformation. During the Council of Trent, the Summa theologica was symbolically placed next to the Bible as a testament to its primary importance in formulating the Tridentine decrees and canons against justification by faith alone and other Protestant doctrines. In the seventeenth century, he was considered the defender of the Roman Catholic theological system by Robert Bellarmine (1542-1621), the greatest anti-Protestant controversialist who influenced many generations of Catholic apologists over the centuries. In 1879 Pope Leo XIII issued the encyclical Aeterni Patris in which he pointed to Thomas as the highest expression of philosophical and theological science. The Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) stipulated that the formation of priests should have Thomas as the supreme guide in their studies: “The students should learn to penetrate them (i.e. the mysteries of salvation) more deeply with the help of speculation, under the guidance of St. Thomas, and to perceive their interconnections” (Optatam Totius [1965] n. 17). Of recent popes, this has already been mentioned. Considering this, what could Pope Francis say but, “Go to Thomas!”

Francis indicated not only the need to study Thomas, but also to “contemplate” the Master before approaching his thought. Thus, to the cognitive and intellectual dimension, he added a mystical one. In this way, he caused Thomas, already a theologian imbued with wisdom and asceticism, to be seen as even more Roman Catholic. This mix best represents the interweaving of the intellectual and contemplative traditions proper to Roman Catholicism.

The International Congress had the exploration of the resources of Thomist thought in today’s context as its theme. Thomism is not just a medieval stream of thought, but a system that is both solid and elastic at the same time. All seasons of Roman Catholicism have found it inspiring for the diverse challenges facing the Church of Rome, including the Reformation first, the Enlightenment project second, and now post-modernity. As a result of the Congress, we will continue to hear more about Thomas and Thomism, not only in historical theology and philosophy, but also in other fields of knowledge that were once far from previous interpretative traditions of Thomas.

In recent years, we have witnessed a growing fascination with Thomas Aquinas and Thomism by evangelical theologians, especially coming from the North American context. They seem to be attracted to the “great tradition” he represents. This phenomenon should be studied because it signals the existence of internal movements within evangelical theological circles. Protestant theology of the 16th and 17th centuries had a critical view of Thomas. In a sense, Thomas could not be avoided, given his stature and importance for theology, but he was read with selective and theologically adult eyes. Then, for various reasons, there has been a certain neglect not only of Thomas but with pre-Reformation historical theology as a whole. Today, in the face of the pressures coming from secularization and the identity crisis felt in some evangelical quarters, Thomas is perceived as a bulwark of “traditional” theology that needs to be urgently recovered. It is often overlooked that Roman Catholicism has considered Thomas as its champion in its anti-Reformation stance and also in its subsequent anti-biblical developments, such as the 1950 Marian dogma of the bodily ascension of Mary. Rome considers Thomas as the quintessentially Roman Catholic theologian and thinker.

“Go to Thomas!” is an invitation that even a growing number of practitioners of evangelical theology would take up. The point is not to uncritically study or absolutely avoid Thomas, but rather to provide the theological map with which one approaches him. It is necessary to develop an evangelical map of Thomas Aquinas. If Rome considers Thomas its chief architect, can evangelical theology approach him without understanding that Thomas stands behind everything Roman Catholicism believes and practices?