April 1st, 2022

Since the sociologist Zygmunt Bauman coined the expression Liquid Modernity (2000), the adjective “liquid” has been applied to almost all phenomena, e.g. liquid society, liquid family, liquid love, etc. In our world, liquidity seems to describe well the vacillating, uncertain, fluid and volatile feature of contemporary life. Everything is mobile, plastic and soft; nothing can be put into solid, stable and lasting casts.

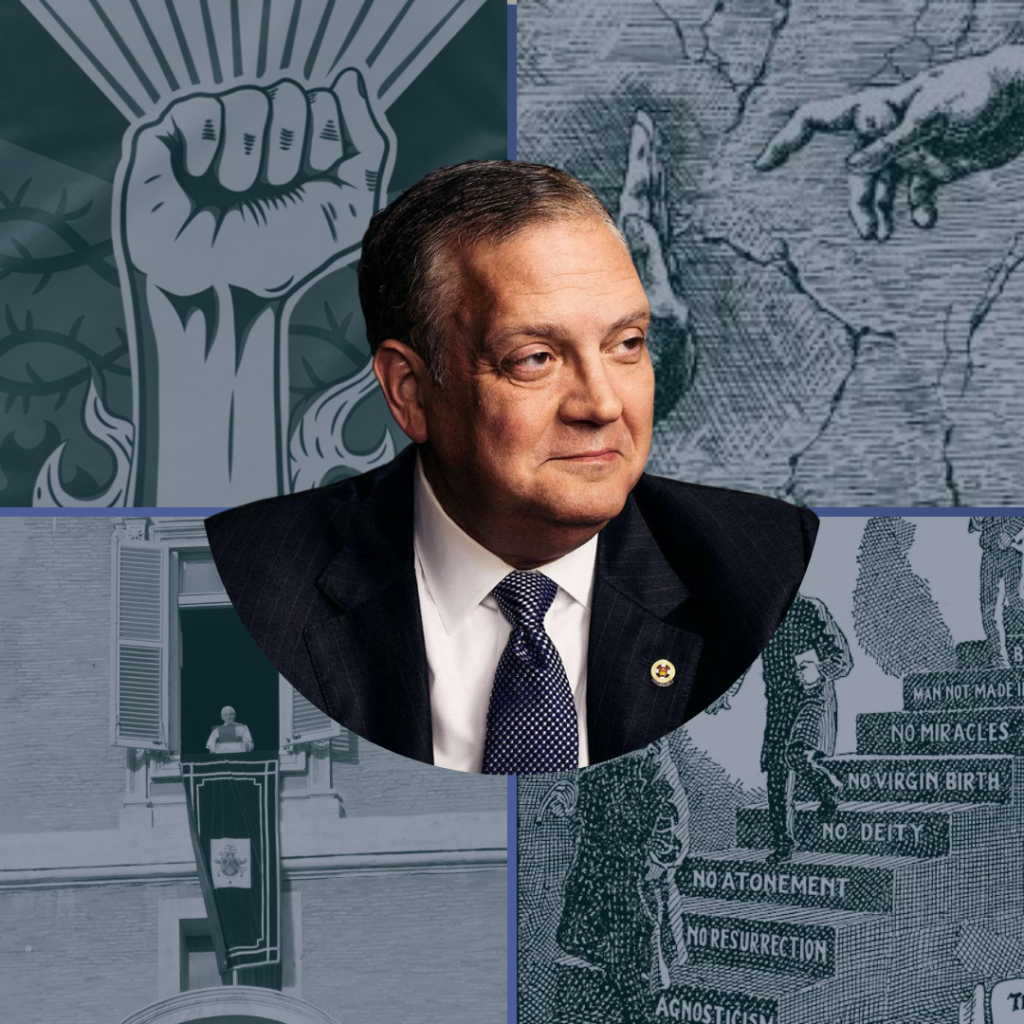

To the already wide range of associations, liquidity has been added as a descriptor for a specific religious tradition, i.e. liquid Roman Catholicism. George Weigel, a conservative American intellectual, talks about it in a worried tone in his article “Liquid Catholicism and the German Synodal Path” (First Things, 16th February 2022).

For some time, Weigel and other exponents of US Roman Catholic traditionalism have expressed their frustration (to put it mildly) at the massive injection of liquidity into Roman Catholicism by Pope Francis. The uncertain teaching on doctrinal and moral subjects of primary importance; a kind of intolerance towards the pre-conciliar liturgy; the constant pickaxing of the Roman Catholic institution with repeated criticism of clericalism; the ways the pope acts outside the box that destabilize customs; the welcoming and merciful message at the expense of the doctrinal and moral requirements of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, etc. All this makes Francis a “liquid” pope who is liquifying an institution that has made its rocky and immutable structure a distinctive trait of its identity.

In addition to Francis, Weigel sees other troubling sources of liquidity in the Roman Catholic church. The article indicates Weigel’s alarm at the requests that are emerging from the “Synodal Path” of the German Catholic Church, including a series of conferences of the Catholic Church in Germany to discuss a range of contemporary theological and organizational questions. Supported by the majority of German bishops, these requests include celibacy becoming optional for clergy (married life being the other option), opening ministries to women (the diaconate first, then one day the priesthood perhaps), recognition (with ecclesiastical blessing) of homosexual unions… these are just some of the proposals that are about to arrive at the Vatican and that have the strength to detonate a bomb in the Roman Catholic Church. There are growing concerns all over the Roman Catholic world about the German “Synodal Path.” In this regard, Francis’ liquidity is just a pale version of the turbo-liquidity that is coming from Catholic Germany.

Weigel and the circles of US Catholic traditionalism witness these processes of liquefaction horrified. For them, Roman Catholicism is a canonically compact religion, sacramentally coherent, institutionally stable, doctrinally integrated. They have in mind a Roman Catholicism that is more “Roman” than “Catholic”, anchored to its unchangeable dogmas, tied to its consolidated tradition, characterized by fidelity and obedience on the part of the faithful, and centered on its ecclesiastical hierarchies. Liquid Roman Catholicism, for them, is a pathology of catholicity that runs the risk of Protestantizing Rome and dispersing its uniqueness in the bewildering contemporary age.

It is interesting to observe these internal conflict dynamics in Roman Catholicism from the outside. Often, in the past, Roman Catholic apologetics contrasted evangelical fragmentation with Roman Catholic solidity, denigrating the former and exalting the latter. It was not a credible argument in the past, but it is even less so today. Roman Catholicism is as divided internally as any other religious movement of global reach. Moreover, traditional Roman Catholic apologetics contrasted the stability of Rome with the volatility of the Reformation. This argument too was superficial and one-sided and it is even more so now. Roman Catholicism goes through significant transformation processes. The fact that Rome is deemed to be “semper eadem” (always the same) needs to be seen in light of its ongoing updating and development.

The key elements to come to terms with in this issue are twofold. First, one needs to consider the dual nature of Roman Catholicism which is, at the same time, “Catholic” (liquid) and “Roman” (solid). Its genius has always been to combine the two faces in order to make them coexist and reinforce each other. Today it is its liquidity that seems to be prevalent, but its solidity will not fail as Roman Catholicism is both. The second key element is the interpretation of the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) which fostered change, as a recent article by Shaun Blanchard has reminded us (Commoweal, 14th March 2022). Vatican II has given Roman Catholicism such an injection of liquidity that today it is impacting the solid structures of Rome as never before. Will the long term outcomes of Vatican II be able to liquefy them completely? Unlikely.

Rome will remain liquid and solid, perhaps in a different arrangement than their present-day combination, but still “Catholic” and, at the same time, “Roman.” Weigel and other Roman Catholic traditionalists dream of a return to a more “Roman” Catholicism: but have they not yet understood that their religion is also increasingly “Catholic” at the same time?