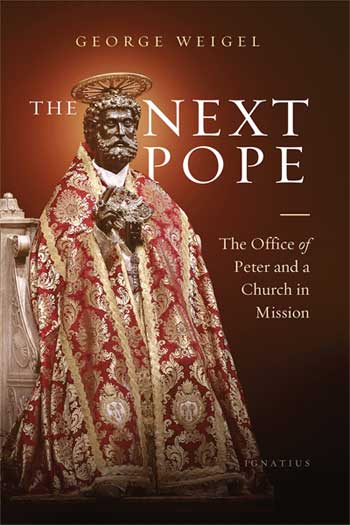

Among the many puzzling things introduced by Pope Francis, his teaching (magisterium) is perhaps the level that was most impacted by the Argentinian Pontiff. The contents of his encyclicals, apostolic exhortations, bulls, speeches, occasional interviews, etc. have been described as “uncertain,” “in motion,” “ambiguous,” “nuanced,” at times even “heretical” – and by Roman Catholics!

Many Roman Catholics (and also many non-Catholic observers), accustomed to associating the papal magisterium with an authoritative, coherent and stable form of doctrinal teaching, are perplexed if not dismayed by a pope who seems both to say and not say, to argue for something and to undermine it, to state one position and then contradict it the next breath. As a Jesuit, Pope Francis tends to use an equivocal style, a dubitative and incomplete form of argumentation, an “open” logic, a colloquial if not casual tone, and a pastoral trait which often lacks clarity and coherence. Officially, the Pope’s teaching is set in the context of the historical traditions of the church. In this sense, nothing changes. In reality, however, Francis is accentuating the developmental and inclusive dynamic of Roman Catholicism as it emerged from Vatican II (1962-1965). According to this trend, while there is a sense in which nothing changes, everything is nonetheless re-thought, re-expressed, and updated. The “Roman” side of the teaching does not change while the “catholic” side does change.

A recent book by the Sicilian Roman Catholic theologian Massimo Naro, Protagonista è l’abbraccio. Temi teologici nel magistero di Francesco (2021: The Protagonist is the Hug. Theological Themes in Francis’ Magisterium) is a helpful guide in the theological universe of Pope Francis. From the outset, Naro readily acknowledges that the theology of Pope Francis is “an innovative proposal” even when compared with the updating trends of the Second Vatican Council.

Above all, the Pope’s vocabulary needs to be taken into consideration. If you want to try to enter the world of Francis, here are his central words: “mother church,” “faithful people of God,” “popular spirituality,” “mercy,” “synodality,” “polyedric ecclesiology,” “processes to initiate,” “existential peripheries,” “humanism of solidarity,” “ecological conversion,” “dialogue,” “fraternity and brotherhood” (p. 19). Not all are new words; some of them are terms that have been already used in Roman Catholic teaching, but are now given a new nuance or a distinct significance by Francis.

Naro further suggests that there are two theological frameworks that give meaning to his words, i.e. the “theology of the people” and the “theology of mercy.” For Francis, theology does not begin with biblical revelation nor from the abstract principles of the official teaching of the Church, but from the common and daily stories of men and women who must be welcomed and affirmed in their particular contexts and life journeys. This attention to the “inside” of the world and to the level where the “people” live pushes him to elevate forms of popular spirituality as authentic religious experiences. He is not scandalized by the “irregular” situations of life in which people find themselves, e.g. divorce, co-habitation, or same-sex relationships. Instead of teaching an external standard (in theology or in morality), the Pope begins where people are assuming that where they are, there is something good that needs to be affirmed.

According to Francis, the “people” are not the passive and obedient recipients of a top-down ecclesiastical magisterium, but active subjects whose religious experiences are true and real (even though not squared with traditional patterns) and therefore need to be part of the teaching itself. The “people” make the teaching as much as the ecclesiastical authorities of the Roman Church promulgate it.

You don’t need to be a trained theologian to catch how this version of the “theology of the people” is far from the evangelical belief that Scripture, as the inspired Word of God, is the source by which God teaches, rebukes, corrects, and trains. And who does He train? Not those who want to affirm their own experiences and lifestyles, but those who wish to repent from sin and reform their lives following the path indicated by the Bible. From a biblical perspective, Francis’ “theology of the people” does not have the external criterion of the Word of God, which questions hearts, practices, sinful habits, etc. and forges a new humanity that is always open to renewal in a process of ongoing sanctification.

Mercy is another keyword in the Pope’s magisterium. In his way of putting it, mercy is “the bridge that connects God and man, opening our hearts to the hope of being loved forever despite the limits of our sins” (Bull of Indiction of the Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy Misericordiae Vultus, n. 2, 2015).[1] In this dense sentence there is a strategic theological point. Among other things, as Cardinal Matteo Zuppi writes in the introduction, the Pope means that “at the center of the biblical message is not sin, but mercy” (p. 16). In Naro’s words, Christian theology must be freed from “hamartiocentrism” (p. 93), i.e., from the centrality of sin. Sin must be replaced by the pervasiveness of God’s mercy which “can help us to break free from hamartiocentrism and to rediscover the tenderness of God” (p. 114). In his view, Pope Francis has replaced sin with mercy at the center of his message.

In the Pope’s theology, sin is at most “the human limit” (p. 91), but not the breaking of the covenant, the rebellion against God, the disobedience to his commandments, or the subversion of divine authority that results in the righteous and holy judgment of God. If sin is a “human limit,” then the cross of Christ did not atone for sin but only manifested God’s mercy in an exemplary way. The words used by the Pope are the same as those of the evangelical faith (e.g. mercy, sin, grace, gospel), but they are given a different meaning than the gospel.

Francis sees everything from the perspective of a metaphysic of mercy that swallows sin without passing through propitiation, expiation, or reconciliation, which the cross of Jesus Christ wrought to give salvation to those who believe in Him. If everything is mercy and sin is only a limit, the resulting message is fundamentally different from the biblical gospel.

The traditional Roman Catholic teaching (from the Council of Trent to the 1992 Catechism of the Catholic Church) conflicts at crucial points with the evangelical faith summarized in the Reformation slogans “Christ Alone,” “Scripture Alone,” and “Faith Alone.” The “popular” and “merciful” account of the gospel taught by Pope Francis is another “catholic” variant of the deviation on which the church of Rome was established and on which, sadly, it continues to move forward.

[1] The English translation of the papal text on the Vatican website is blurred and incorrect. It says “the bridge that connects God and man, opening our hearts to the hope of being loved forever despite our sinfulness” (italics added). However, the Latin official text says “praeter nostri peccati fines” which needs to be translated as “despite the limits or bounds of our sins” as the Italian, French and Spanish versions rightly translate.